Change is coming to heavy vehicle legislation across Australia. Slowly but surely, and with hundreds of pages of documentation along the way. Whether you’re looking for a refresher or for an accessible entry-point, you’ve come to the right place. Read on for all the big bits of the new law, kept in as simple English as we can.

Background and timeline

The Heavy Vehicle National Law (HVNL) looks to keep people, environments, and infrastructure safe, while increasing productivity, efficiency, and innovation. In this industry, which Safe Work Australia statistics show to be one of the deadliest, safety couldn’t be more important. But in the review of the current HVNL, ministers found the law asleep at the wheel in multiple respects.

According to the National Transport Commission (NTC)—the organisational body in charge of the HVNL—the current law was a big leap in its heyday, improving road safety and streamlining the national heavy vehicle (HV) system. But it was also very complicated, prescriptive, and rigid when faced with all the real world’s complexities.

So in 2019, ministers hit the road on a quest to revise this law. Only three years later, though, in August 2022, did they agree on a package of reforms.

All together, the new HVNL law looks to offer:

- Greater simplicity and more options: A simpler law that makes room for both the operators who want to innovate and those who want to just stick to the rules.

- A more flexible framework: A law that can adapt to changing needs, focusing on outcomes and only bringing prescriptive obligations into play when necessary.

- More road network access: A law that helps improve road network access systems.

- Improved fatigue management: A law that simplifies fatigue management, focusing on real risk, obligation clarity, and fairness.

- Clearer duties to driver health: A law that clarifies the chain of responsibility.

- More responsive codes of practice: A law with a more flexible Code of Practice (CoP) that guides the regulator to guide industry to meet their obligations.

- More comprehensive operator certification: A law that includes stronger, more expandable operator certification and a national auditing standard that stops double-ups.

- An adaptable technology and data practice: A law that enables innovative investments in emerging tech while backing it up with a robust certification mechanism.

In a nutshell, the updated legislation sought to become everything its ancestor was not: less prescriptive, more flexible, and simpler.

Also in August 2022, independent director and advisor Ken Kanofski released his report to the Infrastructure and Transport Ministers Meeting (ITMM), which was the culmination of the industry stakeholder consultation he had been assigned in February 2022. More on that later.

Nine months after this package was released—in May 2023—the NTC released its HVNL Decision Regulation Impact Statement (D-RIS), which was a wee 240-page document that dove deep into the 14 changes to the HVNL recommended by transport ministers.

The ministers’ package came in two parts: reforms covered by the updated law, and reforms that sit outside it. The D-RIS covered the former, while the Consultation Regulation Impact Statement (C-RIS) jumped in on the latter.

In October 2023, the C-RIS was released with an invitation: anyone out there could send through their responses to a provided set of questions regarding the possible changes. Submissions closed in November 2023; as of March 2024, 35 are available online.

But we’re gonna park that for a second, and circle back to the D-RIS.

D-RIS summary part 1: problems

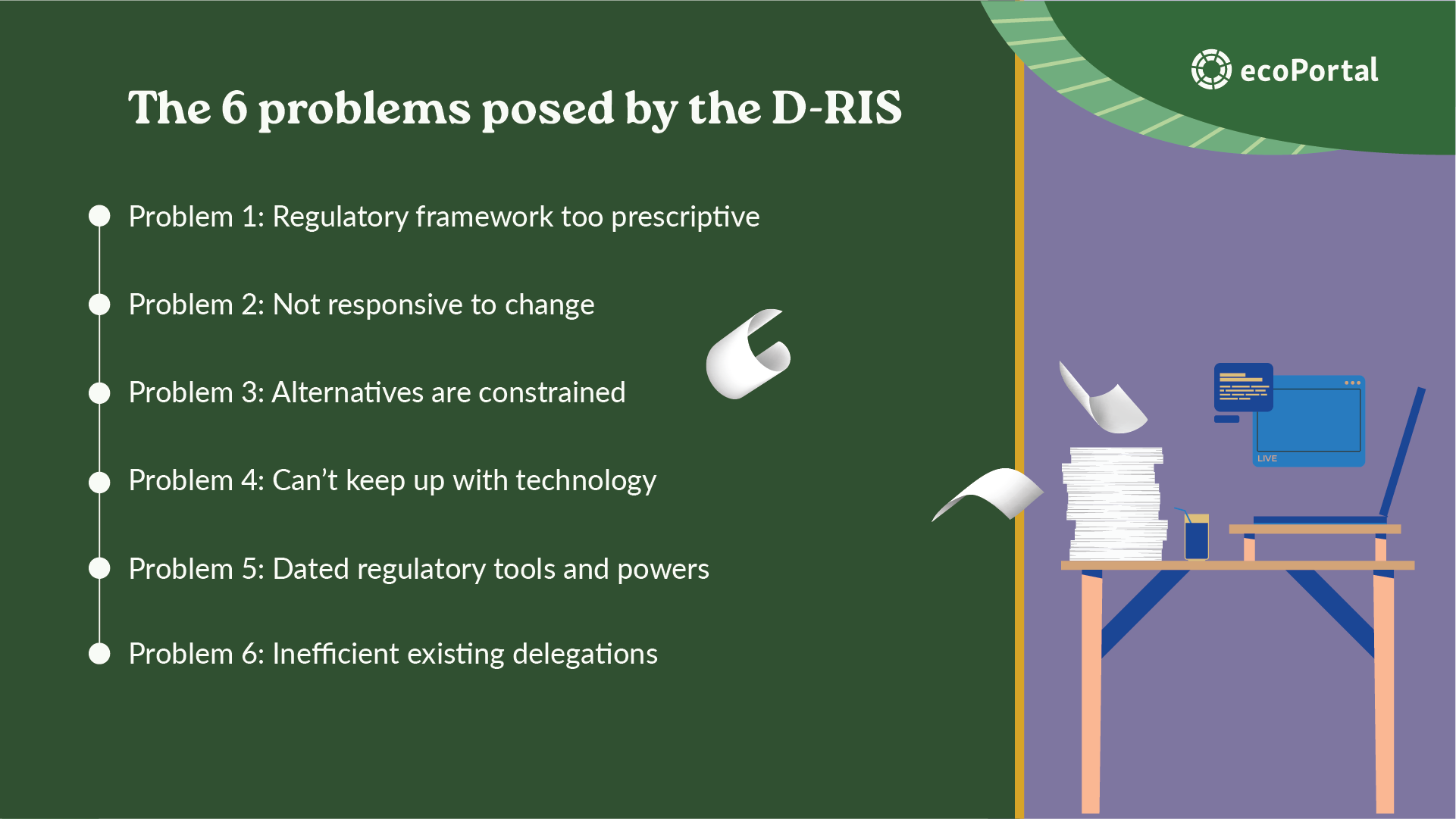

The D-RIS poses 6 problems, and offers 14 recommendations to address these problems.

Problem 1: Regulatory framework too prescriptive

By Australia’s current definitions, heavy vehicles are vehicles that exceed 4.5 tonnes in gross vehicle mass (except for WA and the Northern Territory). But within that, the heavy vehicle industry includes people-movers, produce-movers, and more at short and long distances across urban and rural landscapes.

There are old drivers and new drivers, drivers with pre-existing conditions and drivers that run marathons, drivers with a strong command of English and drivers who might struggle with more advanced texts. This range of contexts calls for a flexibility that still guarantees utmost safety.

Prescriptive requirements form nearly ⅔ of the current HVNL. They do that because such requirements give certainty and make enforcement simpler. But such prescriptiveness can quickly lose meaning.

Problem 2: Not responsive to change

The current law isn’t set up to adapt to the latest innovations or the newest risks, and amendments might take over a year to get going.

Problem 3: Alternatives are constrained

Some operators have found better (read: safer or more efficient) safety management tactics for their needs, but the current law rarely permits these alternatives, and the regulator can’t turn them into new options even if the operator can prove that it’s an improvement.

Problem 4: Can’t keep up with technology

The current law recognises some specific technologies, but has no standard process for recognising new technologies that can help with safety or productivity. There are also no general data-sharing provisions, and more specific clauses are inconsistent.

Problem 5: Dated regulatory tools and powers

Some of the current law’s regulatory tools and powers are too old, too brittle, or too constrained, and some of their processes no longer match best-practice.

Problem 6: Inefficient existing delegations

Some existing authority delegations limit how operators can modernise and manage risk. The existing system for creating new CoPs is very limited in scope, causing a dearth of codes, none of which cover drivers and other parties in the chain of responsibility.

Overall

Other considerations the new law needs to keep on top of:

- Road freight growth

- Changes in demand

- New technologies and the security threats that might tag along

- Supply chain digitisation

- Skill shortages

- Unexpected worldwide events like COVID-19

- Climate change—both responding to its effects and reducing the industry’s impact

The 14 D-RIS recommendations aim to address these six problems to deliver:

- A modern regulatory framework focused on outcomes

- A better National Heavy Vehicle Accreditation Scheme, with tiered assurances

- A framework for data and technology innovations

- An expanded driver duty

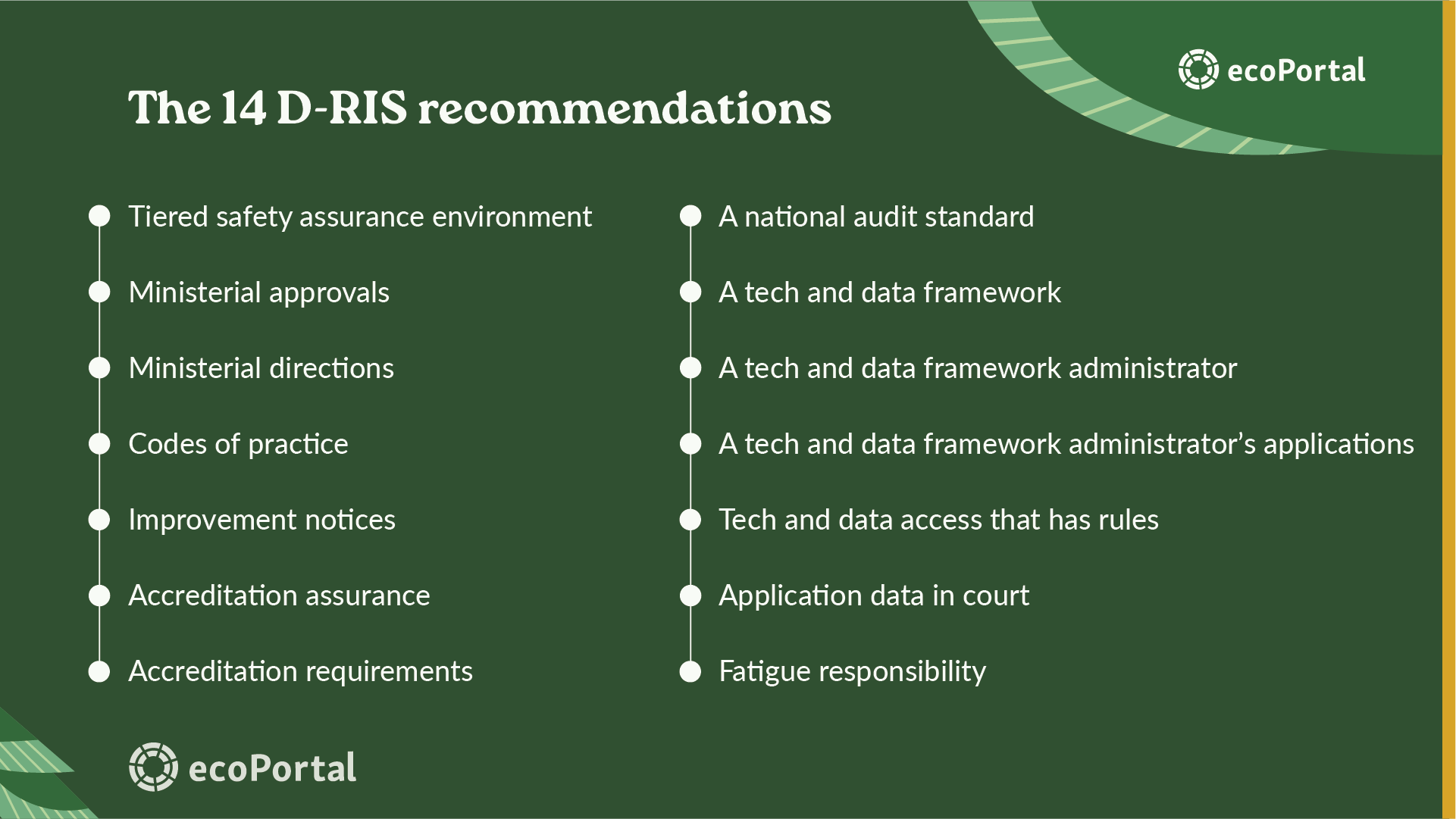

D-RIS summary part 2: recommendations

Most of the following recommendations do not have “direct impacts,” which is to say that they structure room for future change, rather than creating immediate change.

Recommendation 1: Tiered safety assurance environment

Under the more nuanced and flexible system the D-RIS proposes, there are two tiers:

Tier one (baseline tier) is for operators who desire the “simplicity and certainty of prescriptive rules.”

Tier two (compliance tier) is for accredited operators looking for options that keep everyone safe while making more sense for their industry.

Smaller, mid-tier, and larger operators will also have access to more flexible alternative compliance options that suit their scales and structures.

Recommendation 2: Ministerial approvals

The D-RIS proposes a change in the ministers’ powers, with ministers no longer needing to approve accreditation business rules or sleeper berth standards, and now able to approve national audit standards.

The recommendation also suggests giving the regulator more autonomy.

Recommendation 3: Ministerial directions

This recommendation gives ministers the power to:

- Give written directions about issuing alternative compliance options

- Direct regulators to investigate/advise on a public risk

- Direct the regulator to cancel a practice

Recommendation 4: Codes of practice

This recommendation would shift gears from the current industry CoP system and allow the regulator to initiate, develop, and approve new codes. The codes won’t be compulsory.

Recommendation 5: Improvement notices

This recommendation intends to solidify compliance and fix immediate risks with less expense and drama than traditional routes.

Under this recommendation, improvement notices and prosecutions would be able to run at the same time. That means proceedings can start against a party even if an improvement notice has been issued for the same offence, and vice versa.

Recommendation 6: Accreditation assurance

This recommendation would mean that accredited operators can apply for an expandible range of alternative compliance options.

Recommendation 7: Accreditation requirements

This recommendation seeks to make a scalable safety management system a core accreditation requirement. The regulator will review the system in relation to operation size and complexity, as well as the particular freight task. 65% of operators already have a basic safety system in place.

Recommendation 8: A national audit standard

Trying to create a more robust, aligned, and trusted scheme, this recommendation will see a national audit standard developed by the regulator and approved by ministers. Auditors will still be recognised independents.

The standard will cover the “why,” “how,” and “who” of auditing and follow the ISO 19011 Guidelines for Auditing Management Systems standard to support consistent auditing practices. The hope is that this standard will lead to fewer requests for multiple audits—currently a common occurrence.

Recommendation 9: A tech and data framework

This recommendation would enable new technologies and data-sharing schemes to be recognised within an established framework that includes powers, functions, duties, obligations, and rules. It doesn’t replace existing schemes, but does build a formal certification process.

Removing specific tech from primary law so it’s more flexible to future updates, the framework would support data protection, stewardship and assurance, and access and use, for both regulatory and non-regulatory uses.

Recommendation 10: A tech and data framework administrator

Every framework needs its administrator, as well as provisions for ministers to appoint its administrator. Enter recommendation 10.

Administrators will:

- Create, consult on, and approve applications

- Confirm that systems, services, and providers meet application requirements

- Publish a registry of applications and approved providers

- Work with third parties, including deferring to other certifications as needed

Recommendation 11: A tech and data framework administrator’s applications

This Recommendation enables the administrator of recommendation 10 to create applications that outline system approval requirements.

Ministers are the ones to set the conditions that the administrators must follow for these applications. The conditions ensure the tech is fit-for-purpose, and include consultation (with industry, regulators, governments, etc.).

Recommendation 12: Tech and data access that has rules

Recommendation 12 restricts who can access and use gathered data, and ensures that the data-collection process remains transparent. It doesn’t replace or affect existing privacy laws.

Recommendation 13: Application data in court

Under this recommendation, a person can present non-certified application data to a court as evidence of compliance, and it’s the court’s choice what weight to place on the evidence.

Recommendation 14: Fatigue responsibility

Last but certainly not least, the D-RIS recommends to expand the driver’s duty not to drive while fatigued or otherwise unfit. This is a small change: previously, “fatigued” was covered but “otherwise unfit” was not.

Significantly, the recommendation would legally protect drivers who choose to stop driving if they recognise they are not fit for the task, because those in the chain of responsibility cannot force or encourage a driver to break the law.

Next steps

What a journey! The D-RIS covered a lot, but questions remained: What’s to be done about these recommendations? And what of fatigue management, as-of-right road access, and enhanced operator assurance? Those are some pretty big issues to be missing entirely.

Fair questions, but it’s not over yet! Jump to part 2 to find out what happened next.