3 March 2024

Risks of any form can be unexpected and unpredictable; and yet, so often, they are avoidable.

Why is that?

Human nature dictates that we rapidly become accustomed to any new environment we find ourselves in. Sure, we’ll notice something new that happens, but we're hard-wired to adapt quickly to its presence.

In the same vein, when bad things don’t happen, we experience a false sense of security. This makes it incredibly easy to become risk-complacent. When incidents don’t occur, we don’t think of them.

Everything’s fine until it’s not.

It’s easy to become complacent. How many times during your day do you do things on autopilot?

When risk is avoided frequently, we tend to minimise the weight of consequences in our minds. Information intake during these tasks becomes routine, and familiar. In fact, the result of a growing sense of complacency leads to perception of lowered risk.

It’s simple - our experience of our environment adjusts how we perceive it. If we’ve worked for 5 years and had no major accidents, we’ll perceive the risk as lower.

However, research in risk management suggests that the risks don’t actually lower, and that it’s the other way around - the greater the complacency and confidence, the more risk prevails.

It stands to reason therefore, that a culture of complacency is one of the most dangerous things in a workplace. Familiarity with routine tasks and no major incidents, can generate a false sense of confidence amongst employees.

How can we avoid complacency and remain alert?

The One Percent Safer book collates examples of small actions that anyone can implement to create incremental change, 1% at a time. Professor of Decision Sciences at George Washington University and book contributor Dr. Phillipe Delequié addresses the issue of complacency, when he alludes to the popular phrase, “Only the paranoid survive”. His contribution discusses the detrimental effects of employees becoming comfortably numb, and how remaining in a state of paranoia is effective in mitigating the risks.

To help maintain an alert state of mind at all times, Delequié suggests implementing “What-if” thinking exercises. These entail infrequent check-ins while performing a task, ask yourself, ‘What if something goes wrong?”.

It’s a form of contingency planning that helps to avoid becoming comfortably numb. Occasionally checking in and asking questions can be the much-needed dose of cold water to rouse an employee out of their rose-tinted state of mind.

For example, an employee can try this exercise during a mundane task, such as moving furniture in the office. They might ask themselves “What if I trip? What if I strain my back?”.

Asking these very simple questions can help shift an employee out of doing things in autopilot and adjust how they're performing the task.

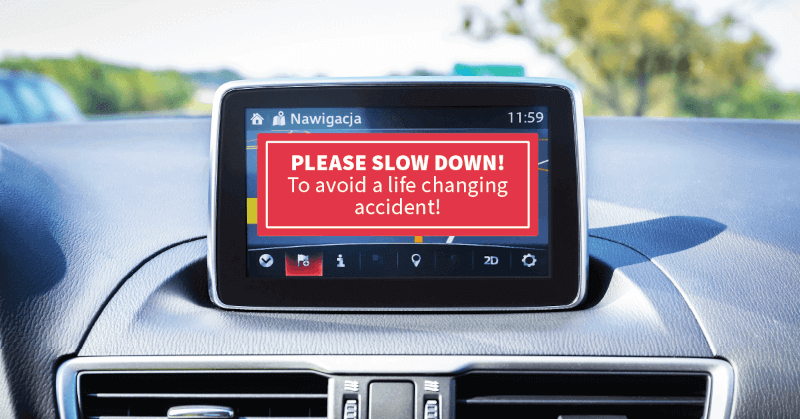

There are various strategies to tackle complacency. Another 1% action comes from contributor Edmund Cheong Peck Huang - Chief Strategy and Transformation Officer at the Social Security Organisation of Malaysia - who recommends incorporating emotive language specifically into navigation applications. Emotive language - that is, specific word choices that elicit an emotional response - is a powerful persuasive device that resonates on a different level with others.

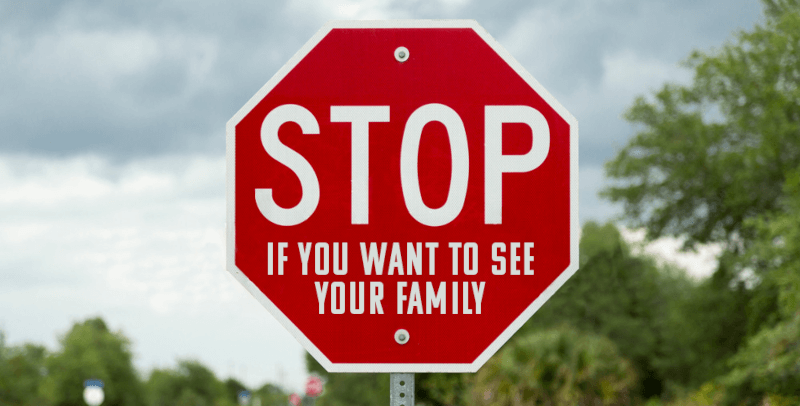

To illustrate, Peck Huang offers the example of using emotive language with truck drivers. For drivers, the message "Please slow down - if you wish to see your friends and family today," coming from their navigation device would be a powerful alternative safety reminder. Using emotive language helps remind us all of what's at stake.

While emotions and the workplace aren’t typically synonymous, the power of emotive language can be harnessed, at a wider scale. Adjusting how we communicate critical-risk-related information to include hair-raising adjectives could help to cut through the noise and jargon of health and safety.

In some cases, automated messages coming from machines or software systems could be adjusted to include eye-catching language, that cuts through the dry monotony of information. When emotive language succeeds in eliciting the desired emotional response from the listener or reader, then you'll have an engaged audience on your hands - far more likely to take their safety seriously.

After all, safety is more than numbers, processes and systems: it should always retain a people-first focus

Perhaps automated messages from machinery, or business-wide systems can include emotive phrasing to cut through the usual monotony of information.

How can the conversation around risk management become emotive?

We can use emotive language to adjust how we frame consequences of risk-taking activities. Reminding people that they may lose their limbs, become paralysed, or risk death are all heavily emotive statements. Reminding them that they risk never seeing family members or friends again - if safety isn’t taken seriously - has a stronger impact. Cutting through any complacency is the critical first step to keeping people safe.

Final Words

Therefore, an effective one percent action health and safety managers can take today, is to have a discussion - either by yourself or with your team - and consider how you might include emotive language in your workplace. Can you incorporate emotive statements in your systems to remind workers of risks?

Are there any areas where a subtle, yet powerful reminder about the importance of taking safety seriously, could be effective?

It’s certainly a valuable discussion to have - and one that might just save lives.

Want to know more about the One Percent Safer Movement in New Zealand? Visit onepercentsafer.co.nz. ecoPortal health and safety engagement software can also help your business. Try a demo or get in touch with the team.